選択的プロゲステロン受容体修飾薬

選択的プロゲステロン受容体修飾薬(Selective progesterone receptor modulator;SPRM)とは、プロゲステロンなどの黄体ホルモンの生物学的標的であるプロゲステロン受容体に作用する薬剤のことである。このような物質が完全な受容体作動薬(例:プロゲステロン、プロゲスチン)や完全な遮断薬(例:アグレプリストン)と異なる特徴は、その作用が組織ごとに異なることである。このように作用が混在しているため、組織特異的に刺激や抑制を受けることになり、合成PR調節剤[1]候補の開発から望ましくない副作用を切り離せる可能性が高まっている[1]。

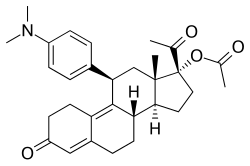

| 選択的プロゲステロン受容体修飾薬 | |

|---|---|

| 薬物クラス | |

| |

| クラス識別子 | |

| 別名 | SPRM |

| 適応 | Emergency contraception, uterine fibroids |

| ATCコード | G03XB |

| 生物学的ターゲット | Progesterone receptor |

| 分類 | Steroidal |

| In Wikidata | |

プロゲステロン受容体

編集受容体

編集プロゲステロン受容体(PR)は、リガンド依存性核内受容体ファミリーに属するタンパク質である[2]。PRには、AとBという2つの主要なアイソフォームと、あまり一般的ではない幾つかのスプライスバリアントが同定されており、これらはすべて同じ8エクソンの遺伝子によってコードされている[3][4][5][6]。他のステロイド核内受容体と同様に、完全長のタンパク質(アイソフォームB)は、4つの機能領域に分けられる。即ち、可変N末端領域に続いて、高度に保存されたDNA結合ドメイン、可変ヒンジ領域、中程度に保存されたリガンド結合ドメインである[3][4]。AF2ドメインと呼ばれるリガンド結合部位は、エクソン4~8で発現しており、253アミノ酸に相当し、その構造はSPRMの開発においては重要な関心事項である[7]。AF2ドメインは、10個のαへリックス(H1, H3~H12)が4枚のβシートと絡み合って3層の束状構造を形成している。H12は、ヘリックス10と11からなる凝縮した連続ユニットで、補助活性化因子の結合過程に関与していることが示唆されている[8]。PRのリガンド結合ドメインは、2つの異なる立体配座の間で平衡を保っている。一つ目は、作動的な構造で、補助活性化因子タンパク質の結合を促し、その結果、遺伝子の転写が促進される。もう一つは遮断的な構造で、これは逆に補助抑制因子の結合を促し、結果的に遺伝子発現を抑制する[8]。プロゲステロンのような完全作動薬は、すべての組織で作動薬としての特性を示し、立体配座の均衡を作動型の方向に強くシフトさせる[8]。逆に、アグレプリストンのような完全遮断薬は、遮断型の方向に平衡を強くシフトさせる。最後に、補助活性化因子と補助抑制因子の濃度の全体的な比率は、細胞の種類によって異なる可能性がある[8]。

Gタンパク質共役受容体

編集2000年に入ってから、プロゲステロンの活性は転写因子だけでなく、膜結合型のGタンパク質共役受容体(7TMPR)によっても媒介されることが明らかになった。この受容体が活性化されると、アデニル酸シクラーゼが阻害され、細胞内のセカンドメッセンジャーであるcAMPの生合成が減少する[7]。

受容体応答後の機序

編集1990年代以降、女性の生殖器系において、2つの主要な受容体アイソマーであるAとBが機能的に異なることが明らかになってきた。この2つのアイソマーの発現プロファイルを調べたところ、月経周期を通じて異なる時期に異なる組織で発現していることが判明した[9]。PR-Bは、卵胞期には卵巣支質と腺上皮で発現が増加し、黄体期には両組織で発現が減少することがわかっている。一方、PR-Aは、卵胞期には両組織で発現が増加し、黄体期後期には間質組織で持続している[9]。これまでの研究で、PR-Bの活性化は乳腺の成長・発達に重要であるのに対し、PR-Aは正常な生殖機能や排卵に重要な役割を果たしていることが判っている。また、in vitro の研究では、同一の条件下で、PR-Bはレポーター遺伝子のより強い転写活性化因子として働き、PR-AはPR-Bや他のステロイド受容体を転写抑制することが明らかになっている[7]。このように異性体間で機能が異なるのには、さまざまな理由が考えられる[10]。まず、PR-Aは、PR-Bに比べてN末端のアミノ酸が164個不足しており、上流セグメントの欠損によりAF-3の活性化機能が奪われ、2つの活性化機能しか持たないことが挙げられる[11]。また、機序の研究では、異性体間で補酵素の会合に違いがあることが判明している。このような機能的な違いに着目し、SPRMの開発では、受容体の片方のアイソフォームを選択的に標的とする薬剤が模索されている[7][10][11]。

SPRMと受容体結合部位との相互作用

編集リガンドとPRの間には、リガンドの結合に重要な特定の相互作用があることが記載されている。受容体に結合したプロゲステロンの結晶学的研究により、プロゲステロンの電子吸引性3-ケト基と、構造的水分子によって位置が保持されているヘリックス-3のGln-725およびヘリックス-5のArg-766残基との間に、重要な水素結合相互作用があることが明らかになった[10]。この相互作用は、他のさまざまなリガンド、例えばミフェプリストン、タナプロゲト、アソプリスニルなどとの相互作用にも存在することが示されており、作動薬と遮断薬の両方の機能に不可欠な相互作用であると考えられる[12]。さらに、プロゲステロンとタナプロゲトは、ヘリックス-3のAsn-719と水素結合することが判っており、より高い選択性と親和性が得られる可能性があるが、SPRMのアソプリスニルはこの残基とは相互作用しないことが判明している[10]。極性残基Thr-894は、プロゲステロンのC20-カルボニル基に近接しているにも拘わらず、これらの化学基の間には水素結合が形成されていない。Thr-894が他のリガンドと相互作用することが判っている点は重要である[10][12]。

さまざまな研究により、17αポケットと呼ばれる疎水性ポケットの存在が報告されている。このポケットは、Leu-715、Leu-718、Phe-794、Leu-797、Met-801、Tyr-890から構成されており、作動薬、遮断薬を問わず、リガンドを拡張する余地があると考えられている。17αポケット、ヘリックス-5のMet-756、Met-759、Met-909は、さまざまなリガンドに対応する驚くべき柔軟性を示しており、プロゲステロン受容体は結合に関して非常に適応的である[10]。作動作用と遮断作用に寄与するヘリックス-12の構造変化を比較した研究では、ヘリックス-3のGlu-723残基との重要な水素相互作用が示された。不活性状態では、Glu-723はMet-908およびMet-909の主鎖アミンと水素結合を形成し、ヘリックス-12の立体配座を安定化させる[10][12]。アソプリスニルのオキシム基が作動薬結合ポケットと相互作用するなど、リガンドが作動効果を発揮すると、前述したヘリックス-12の残基とヘリックス-3の残基の間の水素結合の相互作用が強まり、ドッキングして補助活性化因子が引き寄せられる。しかし、ミフェプリストンなどの遮断薬がこの水素結合システムと相互作用すると、そのジメチルアミン基がMet-909に衝突してヘリックス-12を不安定にし、構造変化を引き起こし、補助抑制因子を引き寄せる結果となる[10][12]。

作用機序

編集SPRMがプロゲステロン受容体(PR)に結合すると、2つの構造状態の均衡がより緊密に保たれるため、細胞環境の違いによって揺れ動きやすくなる。補助抑制因子よりも補助活性化因子の濃度が高い組織では、過剰な補助活性化因子が作動方向に平衡を誘導する。逆に、補助抑制因子の濃度が高い組織では、遮断方向に平衡が進む[13][14]。従って、SPRMは、補助活性化因子が優勢な組織では作動活性を示し、補助抑制因子が過剰な組織では遮断活性を示す。

PRは他のステロイド受容体と同様に、不活性時には受容体自身、熱ショックタンパク質(hsp70、hsp90)、イムノフィリンからなる複合体を形成している[15][16]。ホルモンがリガンド結合ポケットに結合することにより活性化されると、受容体複合体は解離し、核内に取り込まれ、受容体は二量体化するという性質を持つことが示されている。核内では、二量体がDNA上のプロゲステロンホルモン応答因子と相互作用し、遺伝子の発現を上昇または下降させる[17][18][19][20]。さまざまな研究により、受容体の異性体に応じて最大100種類の遺伝子の発現に影響を与えることが明らかにされている[10]。作動薬の作用では、構造変化が起こり、αヘリックス-3、-4、-12が、受容体と基本転写因子との間の橋渡し役である補助活性化因子タンパク質の会合面を形成する[21][22]。しかし遮断薬は、αヘリックス-12がヘリックス-3および-4に対して適切に一体化するのを妨げ、受容体が補助活性化因子と相互作用する能力を低下させ、SMRTやNCoRなどの補助抑制因子の結合を可能にする[23]。作動薬との結合時に補助抑制因子が殆ど働かないことから、Liuら(2002)は、補助活性化因子と補助抑制因子の働きの比率が、化合物が作動薬、遮断薬、あるいは作動薬/遮断薬混合物と見做されるか否かを決定するのではないかと推測している[24]。選択的プロゲステロン受容体修飾薬は、作動薬と遮断薬の混合活性を持つ薬剤として記述されており、従って、作用のメカニズムはこれらの機能のバランスに起因するものであると考えられる。

構造活性相関

編集ステロイド系SPRM

編集左上:作動薬/遮断薬活性の強度

右上:PR/GR選択性

下:O置換によるPR選択性向上

(PR:プロゲステロン受容体)

(GR:糖質コルチコイド受容体)

主に抗黄体ホルモン作用と抗糖質コルチコイド作用の比を改善することに焦点を当てたミフェプリストン類似体の研究は[1][25]、SPRMの発見に繋がった[26]。プロゲステロン受容体(PR)や糖質コルチコイド受容体(GR)への結合には,D環上の17-αプロピニル基やその近傍の修飾が重要な役割を果たす[25][26][27]。17-α領域のわずかな変化により、抗糖質コルチコイド活性が低下した抗プロゲスチンが生成される(αはステロイドの絶対的な立体配置を意味する)[25][26][27][28][29][30]。17-αエチルや17-α(1'-ペンチニル)のような疎水性の17-α置換基は、ミフェプリストンよりも優れた抗黄体ホルモン活性をもたらすようである[27]。また、17α位にFやCF3などの電子吸引性の小さい置換基をパラ位に持つフェニル基を据え置くと、糖質コルチコイド受容体に対する選択性が大きく向上し、得られる化合物の効力も大きくなることが判った。オルト位やメタ位に同じ置換基があると,選択性が低下することも明らかになった。この領域にtert-ブチル基のような嵩高い置換基があると、プロゲステロン性の効力が低下する[29]。

入手可能な生物学的データおよびX線データから、C11位の4-(ジメチルアミノ)フェニル基の置換が作動薬活性と遮断薬活性の程度を決定することが示唆されている[25][26]。メチル基やビニル基のような小さな置換基は強力なPR作動作用をもたらすが[26]、置換されたフェニル誘導体はさまざまな程度の遮断作用をもたらす[26][27][28]。さまざまな窒素複素環で置換された場合、アリール環[31]のメタ原子とパラ原子の領域で負の電位が明確に最大となる化合物が最も作動薬的であり、この領域に電気陰性度の中心がない化合物が最も遮断薬的な活性を持つことが示唆されている[10][31]。

コアとなるステロイド構造の変更は、プロゲステロン受容体への結合様式に影響を与える[29][32]。C7の酸素原子による置換が検討されており、これらのミフェプリストン様オキサステロイドはPRに高い選択性を示したが、ミフェプリストンよりも作用が弱い[29][33]。

非ステロイド系SPRM

編集非ステロイド系のユニークな構造を持つプロゲステロン受容体修飾薬は、現在、開発の初期段階にある。PRの遮断薬としてはさまざまな種類のものが報告されており、下表に示すような顕著な構造の多様性を示している。また、さまざまなリード化合物が新しいプロゲステロン受容体アゴニストとして同定されている[10]。

| 遮断薬 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 作動薬 |

実例

編集以下のものなどがある。

- ウリプリスタル酢酸エステル(日本では未承認。肝毒性あり[34]。)

- アソプリスニル(子宮内膜への副作用のため開発中止。)

- 酢酸テラプリストン(開発中止。)

SPRMは、避妊や緊急避妊、子宮内膜症や子宮筋腫の治療、閉経後の女性におけるホルモン補充療法など、婦人科領域におけるさまざまな用途が提案されている[35]。SPRMの活性は、主にプロゲステロン受容体を介しており、子宮内膜が主な標的組織となっている。従来のプロゲステロン遮断薬とは対照的に、SPRMは遮断薬/作動薬の混合活性により、妊娠を終了させる能力を排除している。SPRMはエストロゲン受容体への親和性が低いため、閉経後の骨量減少を誘発しないと考えられている[9]。SPRMの使用は子宮内膜化生と関連しており、長期的な安全性評価が必要であるとされている[9]。

| Compound | Chemical structure |

|---|---|

| ウリプリスタル酢酸エステル | |

| アソプリスニル | |

| 酢酸テラプリストン |

ウリプリスタル酢酸エステル

編集ウリプリスタル酢酸エステル[36]は、11-βアリール置換型のSPRMで、2009年に欧州で緊急避妊薬として発売され、2010年にFDAから承認された[37]。また、北米および欧州では子宮平滑筋腫の治療薬としても販売されている。緊急避妊薬として、現行の緊急避妊薬の72時間の効力に比べ、無防備な性交後120時間まで効力を発揮することが示されている[35]。また、閉経後の子宮内膜において、プロゲステロン受容体に拮抗する作用があるとされており、更年期障害の治療に使用される可能性があるが、現時点では確認されていない[9]

アソプリスニル

編集アソプリスニルは、ステロイド系の11β-ベンズアルドキシム置換SPRMである[38]。そのオキシム基の形状がin vitro での効力に大きく関与していることが示唆されている[10]。本剤は、平滑筋腫および子宮内膜症の治療薬として提案されており[39]、子宮内膜症治療薬として臨床開発が進められているSPRMの中で、初めて先進的な段階に到達した薬剤であった[40]。

酢酸テラプリストン

編集酢酸テラプリストンは、2014年に子宮筋腫の治療を目的とした第II相臨床試験を実施し[41][42]、子宮内膜症の症状緩和を目的とした第2相臨床試験も実施されていた[43][44][45]。また、化学的予防効果も示唆されている[46]。

効能・効果

編集SPRMは子宮筋腫の治療に有効であったが、子宮内膜肥厚などの副作用が発現したため、投与期間が3~4ヶ月以内に制限されている[47]。

歴史

編集1930年代半ばにプロゲステロンホルモンが発見されて以来[48][49]、特に1970年にその受容体が発見されてからは[50][51]、治療用の遮断薬の開発に大きな関心が寄せられてきた。プロゲスチンとして知られるさまざまなプロゲステロン類似体が合成され、1981年には最初のプロゲステロン受容体遮断薬、ミフェプリストンが発売された[52][53]。しかし、ミフェプリストンはプロゲステロン受容体に比べて糖質コルチコイド受容体への結合親和性が比較的高いため、臨床的には限界があり、副作用のリスクを最小限に抑えるために、より選択性の高いプロゲステロン拮抗薬が求められていた[53][54][55]。その結果、選択的プロゲステロン受容体修飾薬(SPRM)と呼ばれる薬剤が開発された。SPRMは、他のステロイド受容体との相互作用を最小限に抑えながら、組織特異的にプロゲステロン受容体に対して作動薬効果と遮断薬効果を混合して作用する薬剤とされている[56][57]。プロゲステロン遮断薬とは対照的に、混合型の作動薬/遮断薬であるSPRMは、その固有のプロゲステロン遮断薬活性により、妊娠終結効果がないかまたは最小限の効果しかなく、従って、妊娠の可能性を排除することなく婦人科疾患を治療するのに理想的な薬剤である[9]。ステロイド系[58]および非ステロイド系[59]のSPRMが報告されており、最も注目すべき例は、2008年に第3相臨床試験に失敗したアソプリスニルと[38][60]、最初に市販されたSPRMである酢酸ウリプリスタルである[61][62]。

開発

編集ミフェプリストンは、その抗糖質コルチコイド活性により、クッシング症候群、アルツハイマー病、精神病などの治療薬としての可能性が検討されている。また、SPRMは、エストロゲンフリーの避妊薬、子宮筋腫、子宮内膜症など、さまざまな婦人科領域の用途で開発されている[63]。

関連項目

編集参考資料

編集- ^ a b c “Selective progesterone receptor modulator development and use in the treatment of leiomyomata and endometriosis”. Endocrine Reviews 26 (3): 423–38. (May 2005). doi:10.1210/er.2005-0001. PMID 15857972.

- ^ “The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade”. Cell 83 (6): 835–9. (Dec 1995). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-X. PMC 6159888. PMID 8521507.

- ^ a b “The A and B forms of the chicken progesterone receptor arise by alternate initiation of translation of a unique mRNA”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 149 (2): 493–501. (Dec 1987). doi:10.1016/0006-291X(87)90395-0. PMID 3426587.

- ^ a b “Two distinct estrogen-regulated promoters generate transcripts encoding the two functionally different human progesterone receptor forms A and B”. The EMBO Journal 9 (5): 1603–14. (May 1990). doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08280.x. PMC 551856. PMID 2328727.

- ^ “Novel isoforms of the mRNA for human female sex steroid hormone receptors”. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 83 (1–5): 25–30. (Dec 2002). doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(02)00255-8. PMID 12650698.

- ^ “Isoform/variant mRNAs for sex steroid hormone receptors in humans”. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 14 (3): 124–9. (Apr 2003). doi:10.1016/S1043-2760(03)00028-6. PMID 12670738.

- ^ a b c d “Progesterone receptors: form and function in brain”. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 29 (2): 313–39. (May 2008). doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2008.02.001. PMC 2398769. PMID 18374402.

- ^ a b c d “Estrogen and progesterone receptors: from molecular structures to clinical targets”. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 66 (15): 2405–26. (Aug 2009). doi:10.1007/s00018-009-0017-3. PMID 19333551.

- ^ a b c d e f “Selective progesterone receptor modulators and progesterone antagonists: mechanisms of action and clinical applications”. Human Reproduction Update 11 (3): 293–307. (2005). doi:10.1093/humupd/dmi002. PMID 15790602.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l “A new generation of progesterone receptor modulators”. Steroids 73 (7): 689–701. (Aug 2008). doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2008.03.005. PMID 18472121.

- ^ a b “Progesterone receptor and the mechanism of action of progesterone antagonists”. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 53 (1–6): 449–58. (Jun 1995). doi:10.1016/0960-0760(95)00091-d. PMID 7626494.

- ^ a b c d “X-ray structures of progesterone receptor ligand binding domain in its agonist state reveal differing mechanisms for mixed profiles of 11β-substituted steroids”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 287 (24): 20333–43. (Jun 2012). doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.308403. PMC 3370215. PMID 22535964.

- ^ “The partial agonist activity of antagonist-occupied steroid receptors is controlled by a novel hinge domain-binding coactivator L7/SPA and the corepressors N-CoR or SMRT”. Molecular Endocrinology 11 (6): 693–705. (Jun 1997). doi:10.1210/me.11.6.693. PMID 9171233.

- ^ “Coregulator function: a key to understanding tissue specificity of selective receptor modulators”. Endocrine Reviews 25 (1): 45–71. (Feb 2004). doi:10.1210/er.2003-0023. PMID 14769827.

- ^ “Evidence that heat shock protein-70 associated with progesterone receptors is not involved in receptor-DNA binding”. Molecular Endocrinology 5 (12): 1993–2004. (Dec 1991). doi:10.1210/mend-5-12-1993. PMID 1791844.

- ^ “Assembly of progesterone receptor with heat shock proteins and receptor activation are ATP mediated events”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 267 (2): 1350–6. (Jan 1992). doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)48438-4. PMID 1730655.

- ^ “Dimerization of mammalian progesterone receptors occurs in the absence of DNA and is related to the release of the 90-kDa heat shock protein”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 88 (1): 72–6. (Jan 1991). Bibcode: 1991PNAS...88...72D. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.1.72. PMC 50750. PMID 1986383.

- ^ “Mechanisms of nuclear localization of the progesterone receptor: evidence for interaction between monomers”. Cell 57 (7): 1147–54. (Jun 1989). doi:10.1016/0092-8674(89)90052-4. PMID 2736623.

- ^ “Molecular pathways of steroid receptor action”. Biology of Reproduction 46 (2): 163–7. (Feb 1992). doi:10.1095/biolreprod46.2.163. PMID 1536890.

- ^ “Analysis of the mechanism of steroid hormone receptor-dependent gene activation in cell-free systems”. Endocrine Reviews 13 (3): 525–35. (Aug 1992). doi:10.1210/edrv-13-3-525. PMID 1425487.

- ^ “Combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear receptors and coregulators”. Cell 108 (4): 465–74. (Feb 2002). doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00641-4. PMID 11909518.

- ^ “Sequence and characterization of a coactivator for the steroid hormone receptor superfamily”. Science 270 (5240): 1354–7. (Nov 1995). Bibcode: 1995Sci...270.1354O. doi:10.1126/science.270.5240.1354. PMID 7481822.

- ^ “The nuclear corepressors NCoR and SMRT are key regulators of both ligand- and 8-bromo-cyclic AMP-dependent transcriptional activity of the human progesterone receptor”. Molecular and Cellular Biology 18 (3): 1369–78. (Mar 1998). doi:10.1128/mcb.18.3.1369. PMC 108850. PMID 9488452.

- ^ “Coactivator/corepressor ratios modulate PR-mediated transcription by the selective receptor modulator RU486”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (12): 7940–4. (Jun 2002). Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.7940L. doi:10.1073/pnas.122225699. PMC 122999. PMID 12048256.

- ^ a b c d “Synthesis and biological evaluation of partially fluorinated antiprogestins and mesoprogestins”. Steroids 78 (2): 255–67. (Feb 2013). doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2012.09.010. PMID 23178161.

- ^ a b c d e f “Synthesis and biological evaluation of 11' imidazolyl antiprogestins and mesoprogestins”. Steroids 92: 45–55. (Dec 2014). doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2014.08.017. PMID 25174783.

- ^ a b c d “New 11 beta-aryl-substituted steroids exhibit both progestational and antiprogestational activity”. Steroids 63 (10): 523–30. (Oct 1998). doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(98)00060-9. PMID 9800283.

- ^ a b “16 alpha-substituted analogs of the antiprogestin RU486 induce a unique conformation in the human progesterone receptor resulting in mixed agonist activity”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93 (16): 8739–44. (Aug 1996). Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.8739W. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.16.8739. PMC 38743. PMID 8710941.

- ^ a b c d “Parallel synthesis and SAR study of novel oxa-steroids as potent and selective progesterone receptor antagonists”. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 17 (9): 2531–4. (May 2007). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.02.013. PMID 17317167.

- ^ “Synthesis and identification of novel oxa-steroids as progesterone receptor antagonists”. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 17 (4): 907–10. (Feb 2007). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.062. PMID 17169557.

- ^ a b “11-(pyridinylphenyl)steroids--a new class of mixed-profile progesterone agonists/antagonists”. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 16 (6): 2753–63. (Mar 2008). doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2008.01.010. PMID 18243712.

- ^ “Synthesis and SAR study of novel pseudo-steroids as potent and selective progesterone receptor antagonists”. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 19 (14): 3977–80. (Jul 2009). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.095. PMID 19217285.

- ^ “Insight from molecular modeling into different conformation and SAR of natural steroids and unnatural 7-oxa-steroids”. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 18 (13): 3687–90. (Jul 2008). doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.070. PMID 18539027.

- ^ “Suspension of ulipristal acetate for uterine fibroids during ongoing EMA review of liver injury risk”. EMA. 2021年11月11日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Selective progesterone receptor modulators: an update”. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 15 (10): 1403–15. (Jul 2014). doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.914494. PMID 24787486.

- ^ “Immediate pre-ovulatory administration of 30 mg ulipristal acetate significantly delays follicular rupture”. Human Reproduction 25 (9): 2256–63. (Sep 2010). doi:10.1093/humrep/deq157. PMID 20634186.

- ^ “Recent advances in contraception”. F1000Prime Reports 6: 113. (2014). doi:10.12703/p6-113. PMC 4251416. PMID 25580267.

- ^ a b “Asoprisnil (J867): a selective progesterone receptor modulator for gynecological therapy”. Steroids 68 (10–13): 1019–32. (Nov 2003). doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2003.09.008. PMID 14667995.

- ^ “Progesterone antagonists and progesterone receptor modulators: an overview”. Steroids 68 (10–13): 981–93. (Nov 2003). doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2003.08.007. PMID 14667991.

- ^ “Emerging therapy for endometriosis”. Expert Opinion on Emerging Drugs 20 (3): 449–61. (Sep 2015). doi:10.1517/14728214.2015.1051966. PMID 26050551.

- ^ “A Phase 2, Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy Proellex® (Telapristone Acetate) Administered Vaginally in the Treatment of Uterine Fibroids - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov”. clinicaltrials.gov. 2016年1月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Proellex”. ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. 1 April 2021閲覧。

- ^ “Systemic therapy of Cushing's syndrome”. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 9 (1): 122. (Aug 2014). doi:10.1186/s13023-014-0122-8. PMC 4237936. PMID 25091295.

- ^ “Recent scientific advances in leiomyoma (uterine fibroids) research facilitates better understanding and management”. F1000Research 4 (F1000 Faculty Rev): 183. (2015). doi:10.12688/f1000research.6189.1. PMC 4513689. PMID 26236472.

- ^ “Telapristone acetate Withdrawn Phase 2 Trials for Endometriosis Treatment”. drugbank. 2021年11月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Colon cancer and the epidermal growth factor receptor: Current treatment paradigms, the importance of diet, and the role of chemoprevention”. World Journal of Clinical Oncology 6 (5): 133–41. (Oct 2015). doi:10.5306/wjco.v6.i5.133. PMC 4600187. PMID 26468449.

- ^ “Clinical utility of progesterone receptor modulators and their effect on the endometrium”. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 21 (4): 318–24. (Aug 2009). doi:10.1097/GCO.0b013e32832e07e8. PMID 19602929.

- ^ “Organisation of the entire rabbit progesterone receptor mRNA and of the promoter and 5' flanking region of the gene”. Nucleic Acids Research 16 (12): 5459–72. (Jun 1988). doi:10.1093/nar/16.12.5459. PMC 336778. PMID 3387238.

- ^ “The isolation of crystalline progestin”. Science 82 (2118): 89–93. (Aug 1935). Bibcode: 1935Sci....82...89A. doi:10.1126/science.82.2118.89. PMID 17747122.

- ^ Karrer, P.; Schwarzenbach, G. (Jan 1934). “Nachtrag betreffend Acidität und Reduktions-Vermögen der Ascorbinsäure”. Helvetica Chimica Acta 17 (1): 58–59. doi:10.1002/hlca.19340170111. ISSN 1522-2675.

- ^ “Progesterone-binding components of chick oviduct. I. Preliminary characterization of cytoplasmic components”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 245 (22): 6085–96. (Nov 1970). doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62667-5. PMID 5484467.

- ^ Philibert D, Deraedt R, Deutsch G (1981). RU 38486: a potent antiglucocorticoid in vivo. The VII International Congress of Pharmacology. Japan: Tokyo.

- ^ a b “Chick oviduct glucocorticosteroid receptor. Specific binding of the synthetic steroid RU 486 and immunological studies with antibodies to chick oviduct progesterone receptor”. European Journal of Biochemistry 149 (2): 445–51. (Jun 1985). doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1985.tb08945.x. PMID 3996417.

- ^ “The antagonists RU486 and ZK98299 stimulate progesterone receptor binding to deoxyribonucleic acid in vitro and in vivo, but have distinct effects on receptor conformation”. Endocrinology 139 (4): 1905–19. (Apr 1998). doi:10.1210/endo.139.4.5944. PMID 9528977.

- ^ “The influence of antiglucocorticoids on stress and shock”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 761 (1): 276–95. (Jun 1995). Bibcode: 1995NYASA.761..276L. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb31384.x. PMID 7625726.

- ^ “Progesterone receptor modulators and progesterone antagonists in women's health”. Steroids 65 (10–11): 807–15. (Aug 2010). doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(00)00194-X. PMID 11108892.

- ^ “A novel selective progesterone receptor modulator asoprisnil (J867) inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in cultured human uterine leiomyoma cells in the absence of comparable effects on myometrial cells”. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 91 (4): 1296–304. (Apr 2006). doi:10.1210/jc.2005-2379. PMID 16464945.

- ^ “Endocrine pharmacological characterization of progesterone antagonists and progesterone receptor modulators with respect to PR-agonistic and antagonistic activity”. Steroids 65 (10–11): 713–23. (2000-10-01). doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(00)00178-1. PMID 11108882.

- ^ “Nonsteroidal progesterone receptor ligands with unprecedented receptor selectivity”. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 75 (1): 33–42. (Dec 2000). doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(00)00134-5. PMID 11179906.

- ^ “Safety of Treatment of Uterine Fibroids With Asoprisnil - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov”. clinicaltrials.gov. 2016年1月11日閲覧。

- ^ “Long-term treatment of uterine fibroids with ulipristal acetate”. Fertility and Sterility 101 (6): 1565–73.e1–18. (Jun 2014). doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.02.008. PMID 24630081.

- ^ “Assessment Report for Ellaone”. EMA. Nov 2009閲覧。

- ^ “Selective progesterone receptor modulators in reproductive medicine: pharmacology, clinical efficacy and safety”. Fertility and Sterility 96 (5): 1175–89. (Nov 2011). doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.08.021. PMID 21944187.