アメリカアカエイ

アメリカアカエイ(Hypanus americanus)は、トビエイ目アカエイ科の一種。ニュージャージー州からブラジル南部までの西大西洋の熱帯および亜熱帯海域に分布する[2]。体盤は平たく菱形で、背面は茶色、オリーブ色、灰色で、腹面は白色[3]。尾には鋸歯状の毒棘があり、防衛のために使用する。

| アメリカアカエイ | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

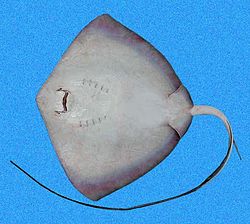

背面

腹面

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 保全状況評価[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| NEAR THREATENED (IUCN Red List Ver.3.1 (2001))

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 分類 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 学名 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hypanus americanus (Hildebrand & Schroeder, 1928) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| シノニム | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| 英名 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Southern stingray | |||||||||||||||||||||

分布域

|

形態

編集海底での生活に適応しており、体盤は扁平な菱形で、角ばっている[4]。背面は成体がオリーブ色から緑色、幼体では濃い灰色で、腹面は白色[4][5]。翼のような胸鰭で海底を進む。尾は細く、基部には長い鋸歯状の毒棘がある[6]。刺されても命にはかかわらないが、非常に痛い。眼は頭頂部にあり、後方に噴水孔がある。噴水孔により海底に埋まっていても水を取り込み呼吸を行うことができる[4][6]。雌の方が大きく、体盤幅は150cmに達するが、雄は最大でも67cm[7][8]。

生態

編集夜行性の肉食魚で、口から水を噴射したり胸鰭を動かしたりして、底に隠れた獲物を見つける。底魚であり、単独またはつがいで見られることが多く、出産場所と考えられる特定の浅場では、1平方キロメートルあたり最大245匹の個体群密度に達すると推定されている[9]。 胸鰭を波打たせて素早く泳ぐことで、天敵からの逃走と餌の捕食に役立っている。行動範囲は非常に広い。その高い遊泳力により、潮の流れに沿って泳ぐことができ、捕食の効率を上げている。交尾、捕食者からの防衛、休息の際群れを作ることがある[10][11][12][13][14]。

摂餌

編集解剖の結果、胃の内容物は小魚、ワーム、甲殻類、二枚貝などであった[15]。遊泳力も高いため、素早い獲物も捕食できる。日和見的な捕食者であり、常に餌を探し回っている[16]。

防衛

編集捕食者を避けるため、海底に埋まっている。尾の毒棘を用い、人間や、ヒラシュモクザメなどの捕食者を撃退する[17]。

他生物との関係

編集メキシコ湾などの沿岸地域では、本種が底を掘ることで出てきた魚を捕食するため、ミミヒメウが本種の後を泳ぐ行動が知られている[18][19][20][21][22][23]。

繁殖

編集卵胎生であり、受精卵は胎内で成長する。胚は発生初期に卵黄嚢から栄養を受け取り、卵黄嚢が吸収された後は子宮分泌液から栄養素を摂取する。雌は毎年繁殖し、妊娠期間は7-8か月[24]。飼育下では、妊娠は135日から226日続き、産仔数は2-10であった[7]。

野生での交尾の観察記録は少ないが、2尾の雄が1尾の雌を追いかけ、雌の鰭に噛みつき交尾を行ったという記録がある。雌は出産後すぐに再び交尾できる[25]。

性成熟と成長

編集バハマのビミニとケイマン諸島のグランドケイマンでの観察によると、性成熟の年齢には、地理的位置が影響する。飼育下の場合、雌は5-6歳で妊娠し、成熟したとされ、雄は3-4歳で成熟したとされた。飼育下では年に2回、野生では年に1回出産する。母親の大きさと産仔数には正の相関がある[25]。出産場所と仔エイの育つ場所は異なる。出産場所は例えばベリーズにあり、雌が交尾と出産のため集まる。ある研究では、5月、11月、12月の間に水深10-20mの岩礁で仔エイが捕獲された。これらの仔エイはその場所で成長していると考えられた[7][26]。

コミュニケーション

編集嗅覚が強いため、フェロモンを用いてコミュニケーションを取る。雄は交尾の前に雌に触れたり鰭を噛んだりする。雌は出産後、総排出腔で生成されると考えられるフェロモンを放出し、雄を引き寄せる。出産後すぐに交尾できるため、これが性フェロモンである可能性がある。頭の周りに多くのロレンチーニ器官を持ち、微弱な電流を感知して獲物を探す。聴覚だけでなく水中の振動を感知するメカニズムも持っている[25][27]。

人とのかかわり

編集グランドケイマン、ケイマン諸島、アンティグア島などカリブ海の多くの地域では、ダイバーやシュノーケラーと一緒に泳ぎ、スティングレイシティやサンドバーなどで手から餌を与えられる。タークス・カイコス諸島では、Gibbs Cayと呼ばれる場所で手から餌を与えられる[13]。 人の腕に抱かれたり、切った魚を食べる個体もいる。地元住民はこれらの大人しい個体を犬のように思っており、この餌付けが本種の行動や生態に悪影響を及ぼす危険もある。

比較的丈夫だが、巨大な水槽が必要で水槽内の生物を捕食してしまうため、アクアリウムでの飼育は難しい[28]。また、カリフォルニア州ヴァレーホのシックスフラッグス・ディスカヴァリーキングダムやニューヨーク州リバーヘッドのロングアイランド水族館などの公立水族館やアニマルテーマパークで飼育され、タッチプールで撫でることができる。水族館では、雌が鰭を噛み合っているのが目撃されている。水族館での繁殖例もある[28]。

画像

編集脚注

編集- ^ Carlson, J.; Charvet, P.; Blanco-Parra, MP, Briones Bell-lloch, A.; Cardenosa, D.; Derrick, D.; Espinoza, E.; Morales-Saldaña, J.M.; Naranjo-Elizondo, B. et al. (2020). “Hypanus americanus”. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T181244884A104123787. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T181244884A104123787.en 19 November 2021閲覧。.

- ^ Dasyatis americana Hildebrand & Schroeder, 1928. FishBase

- ^ Bigelow, H. and Sschroder, W. (1953) Fishes of the Western North Atlantic. Sawfishes, guitarfishes, skates and rays. Mem. Sears Found. Mar. Res. 1, 1-558.

- ^ a b c “Dasyatis americana”. Florida museum. 2023年11月25日閲覧。

- ^ Lieske, E. and Myers, R. (2002) Coral Reef Fishes: Indo-Pacific and Caribbean. HarperCollins Publishers, London

- ^ a b Carpenter, K.E. (2001) The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Atlantic, Volume 1. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

- ^ a b c Henningsen, A.D. (2000). “Notes on reproduction in the southern stingray, Dasyatis americana (Chondrichthyes: Dasyatidae), in a captive environment”. Copeia 2000 (3): 826–828. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2000)000[0826:NORITS]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 1448353.

- ^ McEachran, J. & de Carvalho, M. (2002) "Dasyatidae". In: K.E. Carpenter (ed.). The living marine resources of the Western Central Atlantic. Volume 1. Introduction, molluscs, crustaceans, hagfishes, sharks, batoid fishes and chimaeras. pp. 562–571.

- ^ Tilley, Alexander; Strindberg, Samantha (2013). “Population density estimation of southern stingrays Dasyatis americanaon a Caribbean atoll using distance sampling”. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 23 (2): 202. doi:10.1002/aqc.2317.

- ^ Semeniuk, Christina A. D.; Speers-Roesch, Ben; Rothley, Kristina D. (2007). “Using Fatty-Acid Profile Analysis as an Ecologic Indicator in the Management of Tourist Impacts on Marine Wildlife: A Case of Stingray-Feeding in the Caribbean”. Environmental Management 40 (4): 665–77. Bibcode: 2007EnMan..40..665S. doi:10.1007/s00267-006-0321-8. PMID 17638047.

- ^ Cartamil, D. P.; Vaudo, J. J.; Lowe, C. G.; Wetherbee, B. M.; Holland, K. N. (2003). “Diel movement patterns of the Hawaiian stingray, Dasyatis lata: implications for ecological interactions between sympatric elasmobranch species”. Marine Biology 142 (5): 841. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1014-y.

- ^ Rosenberger, L. (2001). “Pectoral fin locomotion in batoid fishes: Undulation versus oscillation”. The Journal of Experimental Biology 204 (Pt 2): 379–94. doi:10.1242/jeb.204.2.379. PMID 11136623.

- ^ a b Semeniuk, CAD; Rothley, KD (2008). “Costs of group-living for a normally solitary forager: effects of provisioning tourism on southern stingrays Dasyatis americana”. Marine Ecology Progress Series 357: 271–282. Bibcode: 2008MEPS..357..271S. doi:10.3354/meps07299.

- ^ Semeniuk, Christina A.D.; Haider, Wolfgang; Cooper, Andrew; Rothley, Kristina D. (2010). “A linked model of animal ecology and human behavior for the management of wildlife tourism”. Ecological Modelling 221 (22): 2699. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.07.018.

- ^ UWI,The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago

- ^ Gilliam, D. & Sullivan, K. (1993). “Diet and feeding habits of the Southern stingray”. Bulletin of Marine Science 52 (3): 1007–1013.

- ^ Pikitch, E.; D. Chapman; E. Babcock; M. Shivji (2005). “Habitat use and demographic population structure of elasmobranchs at a Caribbean atoll (Glover's Reef, Belize)”. Marine Ecology Progress Series 302: 187–197. Bibcode: 2005MEPS..302..187P. doi:10.3354/meps302187.

- ^ Snelson, F.; S. Gruber; F. Murru; T. Schmid (1990). “Southern Stingray, Dasyatis americana: Host for a Symbiotic Cleaner Wrasse”. Copeia 1990 (4): 961–965. doi:10.2307/1446479. JSTOR 1446479.

- ^ Sazima, C.; J. Krajewski; R. Bonaldo; I. Sazima (2007). “Nuclear-follower foraging associations of reef fishes and other animals at an oceanic archipelago”. Environmental Biology of Fishes 80 (4): 351–361. doi:10.1007/s10641-006-9123-3.

- ^ Saunders, D. (1958). “The occurrence of Haemogregarina bigemina Laveran and Mesnil, and H. dasyatis n. sp. in marine fish from Bimini, Bahamas”. Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 77 (4): 404–412. doi:10.2307/3223863. JSTOR 3223863.

- ^ Kohn, A.; S. Cohen; G. Salgado-Maldonado (2006). “Checklist of Monogenea parasites of freshwater and marine fishes, amphibians and reptiles from Mexico, Central America and Caribbean”. Zootaxa 1289: 1–114.

- ^ Kajiura, S.; L. Macesic; T. Meredith; K. Cocks; L. Dirk (2009). “Commensal Foraging Between Double-crested Cormorants and a Southern Stingray”. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 121 (3): 646–648. doi:10.1676/08-122.1.

- ^ Brooks, D. & Mayes, M. (1980). “Cestodes in four species of euryhaline stingrays from Colombia”. Proceedings of the Helminthological Society of Washington 47: 22–29.

- ^ Ramirez Mosqueda, E., Perez Jimenez, J. C., & Mendoza Carranza, M. (2012). Reproductive parameters of the southern Stingray Dasyatis americana in southern Gulf of mexico. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research, 40(2), 335–344. https://doi.org/10.3856/vol40-issue2-fulltext-8

- ^ a b c Chapman, Demian D.; Corcoran, Mark J.; Harvey, Guy M.; Malan, Sonita; Shivji, Mahmood S. (2003). “Mating behavior of southern stingrays, Dasyatis americana (Dasyatidae)”. Environmental Biology of Fishes 68 (3): 241. doi:10.1023/A:1027332113894.

- ^ Henningsen, Alan D.; Leaf, Robert T. (2010). “Observations on the Captive Biology of the Southern Stingray”. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 139 (3): 783. doi:10.1577/T09-124.1.

- ^ Gardiner, J., R. Hueter, K. Maruska, J. Sisneros, B. Casper, D. Mann, L. Dernski. (2012). "Sensory Physiology and Behavior of Elasmobranchs", pp. 349-401 in J Carrier, J Musick, M Heithaus, eds. Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives, Second Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- ^ a b Michael, Scott (2001). Aquarium Sharks & Rays. Neptune City, NJ: T.F.H Publications, Inc.