エルニーニョ

この項目「エルニーニョ」は翻訳されたばかりのものです。不自然あるいは曖昧な表現などが含まれる可能性があり、このままでは読みづらいかもしれません。(原文:en:El Niño21:32, 23 December 2021) 修正、加筆に協力し、現在の表現をより自然な表現にして下さる方を求めています。ノートページや履歴も参照してください。(2022年1月) |

エルニーニョ(スペイン語:El Niño 語意は「神の子」[注釈 1])またはエルニーニョ現象(エルニーニョげんしょう)とは、エルニーニョ・南方振動(ENSO) での温暖な局面を指す用語で、南米の太平洋岸沖合を含む中央太平洋および東中部太平洋の赤道域(概ね日付変更線と西経120度の間)にて発達する暖かい海流が関与しているもの[注釈 2]。

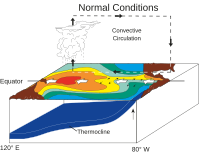

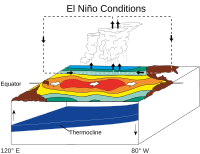

ENSOとは、中央太平洋および東太平洋の熱帯域で発生する海面水温(SST)が上昇しては下降する振動である。その温暖局面にあたるエルニーニョは西太平洋に高い気圧をもたらし、東太平洋には低い気圧をもたらす。エルニーニョの状態は数年にわたって続くことが知られており、記録ではその周期が2-7年継続することが示されている。エルニーニョの発達時期は、9月から11月にかけて降雨が発生する[要説明][3]。対してENSOの寒冷局面はラニーニャ(スペイン語で「女の子」の意)と呼ばれ、東太平洋の海面温度が平均を下回り、東太平洋で気圧が高くなって西太平洋では低くなる。エルニーニョとラニーニャの双方を含むENSOの周期が、気温と降雨における世界規模の変化を引き起こしている[4][5]。

とりわけ国境を太平洋と接しており農業と漁業に依存する発展途上国が、一般的に最もその影響を受ける。この局面になると、南米付近の太平洋にある暖水域が多くの場合クリスマス頃に最も暖かくなる[6]。元々のフレーズ「El Niño de Navidad」は数世紀前に生まれたもので、ペルーの漁師がキリスト降誕祭にちなんでこの気象現象を命名した[7][8]。

概要

編集もともと「エルニーニョ」という用語は、クリスマス時期にペルーとエクアドルの沿岸を南に流れる毎年の小規模な暖かい海流を指すものだった[9]。しかし、歳月が経つにつれてこの用語は進化し、現在ではエルニーニョ・南方振動での温暖かつ好ましくない局面および中央太平洋と東太平洋の熱帯域における海面の温暖化や平均を上回る海面水温を指すものとなっている[10][11]。この温暖化が大気循環の遷移を引き起こしており、インドネシア、インド、オーストラリア上空では降雨量が減少し、太平洋熱帯域の上空では降雨量が多くなって熱帯低気圧の形成も増加する[12]。海面辺りを吹く貿易風は、平年だと赤道に沿って東から西に吹いているが、これが弱まったり他の方角から吹くようになる[11]。

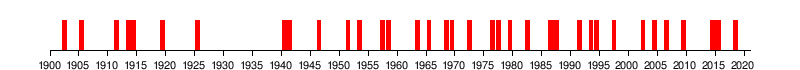

エルニーニョは数千年にわたって発生していると考えられている[13]。例えば、エルニーニョは現在のペルーにあったモチェ文化に影響を及ぼしたと思われる。また科学者たちは、エルニーニョによって引き起こされた海面温度の上昇と降雨量の増加による化学的兆候を約13,000年前のサンゴ標本で発見した 。1525年頃、フランシスコ・ピサロはペルーに上陸した際に砂漠での降雨を記述しており、これがエルニーニョの影響を最初に書き留めた記録とされている。現代の調査および再分析技術によって、1900年以降に少なくとも26回のエルニーニョ現象が起こっており、1982-83,1997-98,2014-16年の現象が記録上最も強いものだったことが判明した[14][15][16]。

現在、エルニーニョ現象を構成する要件について各国が異なる閾値を持っており、閾値はその国独特の利害と絡み合ったものである[17]。例えば、オーストラリア気象局はエルニーニョ監視海域3および3.4の貿易風、南方振動指数(SOI)、気象モデル、海面温度を見てからエルニーニョを宣言する[18]。米国気候予測センター(CPC)やコロンビア大学の地球研究所 は、エルニーニョ監視海域3.4の海面温度や太平洋熱帯域の大気を観察してアメリカ海洋大気庁の海洋ニーニョ指数が数シーズン連続で+0.5°Cを超えるとエルニーニョだと予測している[19]。ところが日本の気象庁は、エルニーニョ監視海域3の海面水温基準値との偏差にあたる5か月移動平均値が +0.5℃以上の状態で6か月持続する場合に「エルニーニョ現象が発生」と表現している[20]。ペルー政府は、エルニーニョ監視海域1と2の海面温度偏差が少なくとも3ヶ月間+0.4°C以上となった場合に沿岸のエルニーニョが進行中だと宣言している[21] (エルニーニョ監視海域については後述の海域図を参照)。

エルニーニョ現象には「強くなる、長くなる、短かくなる、弱くなる」のいずれを支持する研究もあるため、気候変動がエルニーニョ現象の発生、強さ、期間に影響をどう及ぼすかに関するコンセンサスが存在しない[22][23]。

発生

編集

エルニーニョ現象は何千年も前から発生していると考えられている[13]。例えば、エルニーニョは雨を降らせまいと人身御供をしたモチェ文化に影響を与えたと考えられている[24]。

1900年以降少なくとも30回のエルニーニョ現象が発生し、1982-83,1997-98,2014-16年の現象が記録上で最も強大だと考えられている[14][15]。2000年以降では2002-03, 2004-05, 2006-07, 2009-10, 2014-16[14], 2018-19年にエルニーニョ現象が観測された[25][26]。

典型的には、この異常が2-7年の不規則な間隔で発生しており、9ケ月-2年ほど継続する[27]。平均的な期間の長さは5年である。この温暖な状態が7-9か月にわたって発生するとエルニーニョ「状態(condition)」に分類され、その継続時期が長い場合にエルニーニョ「期間(episode)」に分類される[28]。

強いエルニーニョ期間の最中に、極東太平洋の赤道域全体で海面温度の二次ピークが最初のピークに続いて起こることが時々ある[29]。

文化史との関連

編集少なくとも過去300年間でENSO状態が2-7年間隔で発生しているものの、その大半は振れ幅が弱い。1万年前の完新世初期におけるエルニーニョ現象が強かったとする証拠も存在する[30]。

エルニーニョは、モチェ文化をはじめ先コロンブス期のペルー文化を崩壊に至らせた可能性がある[31]。近年の研究では、1789年から1793年にかけての強大なエルニーニョの影響がヨーロッパで作物収穫の不作を引き起こし、これがフランス革命勃発を助長したと示唆されている[32]。1876-77年のエルニーニョで生じた極端な天候は、19世紀の最も致命的な飢饉の原因となったとされ[33]、1876年の飢饉では中国だけで最大1300万人が死亡した[34]。

気候を指す「エルニーニョ」という用語の記録された最初期の言及は1892年、南へ向かう暖流がクリスマスの頃に最も顕著だったためペルー人船員が「エルニーニョ」と名付けた、とカミロ・カリーリョ海軍大尉がリマでの地理学会会議で語った[35]。この現象はグアノ産業や海洋生物の生物圏に依存する他の事業に及ぼす影響から、長年にわたって関心が寄せられていた。早くも1822年には、フランスのフリゲート艦(La Clorinde)で地図製作をしていたジョセフ・ラルティゲがペルー海岸沿いを南に移動するこの「逆流」とその有用性を指摘した記録が残っている[36][37][38]。

1888年にチャールズ・トッドは、インドとオーストラリアの干ばつが同時に起こる傾向があることを示唆した[39]。ノーマン・ロッカーも1904年に同じことを指摘した[40]。1894年にビクトル・エギグレン(1852-1919)、1895年にフェデリコ・アルフォンソ・ペゼット(1859-1929)によって洪水とエルニーニョとの関連が報告された[41][37][42]。1924年にギルバート・ウォーカー (ウォーカー循環の由来となった人物) が「南部振動」を造語し[43]、一般的には彼や気象学者ヤコブ・ビヤークネス などがエルニーニョの影響を特定したと評されている[44]。

1982-83年の強大なエルニーニョが科学界からの関心を高めることになった。1991-95年の時期は、複数のエルニーニョがこれほど急に連続発生することが稀であり異例となった[45]。1998年の特に激しいエルニーニョ現象は、世界のサンゴ礁体系の推定16%が死滅する原因となった。この時は通常のエルニーニョ現象における+0.25°C上昇と比較して、一時的に+1.5°Cの温度上昇が起きていた[46]。それ以来、世界規模で大量のサンゴ白化現象が普遍的となり、あらゆる水域が「重度の白化」被害にさらされている[47]。

多様性

編集エルニーニョ現象には複数のタイプがあり、正統的な東太平洋型それから「モドキ」な中央太平洋型の2つが最も注目され、受け入れられている[48][49][50]。これら異なるタイプのエルニーニョ現象は、熱帯太平洋の海面温度異常が最大となった場所によって分類される[50]。例えば、正統な東太平洋型での最も強い海面温度異常はその位置が南米沖合となり、モドキな中央太平洋型での最も強い異常位置は日付変更線付近である[50]。ただし、単一のエルニーニョ期間に海面温度異常が最大となる水域は変わってしまう可能性がある[50]。

東太平洋(EP)エルニーニョ[51]とも呼ばれる伝統的なエルニーニョは、東太平洋の温度異常を伴う。しかし、直近20年間で通常とは異なるエルニーニョが複数観察され、通例だと温度異常になる場所(ニーニョ監視海域1と2)は影響を受けないのに、中央太平洋(同3.4)で異常が発生している[52]。この現象は、中央太平洋(CP)エルニーニョ[51]や「日付線」エルニーニョ(国際日付変更線付近で異常が発生するため)またはエルニーニョ「モドキ」[53](「似ているけど異なる」という日本語が由来)とも呼ばれている[54][55][56][57]。

CPエルニーニョの影響は伝統的なEPエルニーニョのものとは異なる。例えば、近年発見されたエルニーニョは頻繁に上陸するより多くのハリケーンを大西洋にもたらしている[58]。

ただし、この新しいENSOの存在に異論を唱える研究も多い。実際には発生が増加していない、統計的に区別するには信頼性の高い記録が足りないとするもの[59][60]、他の統計アプローチを使うと区別や傾向が見つからないとするもの[61][62][63][64][65] 、標準的なENSOと極端なENSOといった他の種類で区別すべきとするものもある[66][67]。

中央太平洋を発端として東方向に移動したエルニーニョの最初の記録は1986年である[68]。近年の中央太平洋エルニーニョは1986-87, 1991-92, 1994-95, 2002-03, 2004-05 ,2009-10年に発生した[69]。さらに1957-59[70],1963-64, 1965-66, 1968-70, 1977-78,1979-80年の現象が「モドキ」だったという[71][72]。一部資料では、2014-16年のエルニーニョも中央太平洋エルニーニョだと述べている[73][74]。

地球規模の気候に及ぼす影響

編集エルニーニョは、地球規模の気候に影響を与えて通常の気象パターンを混乱させ、その結果ある場所では激しい嵐をもたらしたり、他の場所では干ばつをもたらす可能性がある[75][76]。

熱帯低気圧

編集大半の熱帯低気圧は赤道に近い亜熱帯高圧帯の側で形成され、そこから高圧軸を越えて極方向に移動したのち偏西風のメインベルトに再帰する[77]。日本の西部および韓国域では、エルニーニョおよび中立な年の9-11月に熱帯低気圧の影響を多く受ける傾向がある。エルニーニョの年には亜熱帯高圧帯の尾根が東経130°付近で居座る傾向があり、日本列島が特に影響を受けることになる[78]。

大西洋域内では、大気中の偏西風が強まることによって鉛直ウインドシアが増加し、これが熱帯低気圧の発生および発達を抑制する[79]。大西洋上空の大気もまたエルニーニョ現象の時期に乾燥かつ安定的になり、これも熱帯低気圧の発生や発達を食い止める[79]。東太平洋海盆では、エルニーニョ現象が東の鉛直ウインドシアを減らす一因となっており、平年以上にハリケーン活動を誘発してしまう[80]。ただし、この海域におけるENSOの影響は多彩であり、背景にある気候パターンに強く影響される[80]。西太平洋海盆ではエルニーニョ現象の最中に熱帯低気圧が形成される場所に変化が生じ、熱帯低気圧の形成が東へ遷移するも、毎年の発現数はさほど変わらない[79]。この変化の結果として、ミクロネシアでは熱帯低気圧の影響を受ける可能性が高まり、中国では熱帯低気圧のリスクが低下する[78]。熱帯低気圧が形成される場所の変化は南太平洋の東経135°-西経120°間でも起こり、熱帯低気圧はオーストラリア地域よりも南太平洋海盆で発生する可能性が高い[12][79]。この変化の結果、熱帯低気圧はクイーンズランド州に上陸する可能性が50%低下し、ニウエ、フランス領ポリネシア、トンガ、ツバル、クック諸島などの島国では熱帯低気圧のリスクが高まる[12][81][82]。

熱帯大西洋での影響

編集赤道太平洋のエルニーニョ現象が、概ね次の春夏における熱帯北大西洋の温暖と関連していることを示す気候研究がある[83]。エルニーニョ現象の約半分が春季に十分持続すると、夏に西半球の暖水域が異常に大きくなる[84]。時には、エルニーニョが南米上空の大西洋ウォーカー循環に及ぼす影響として西赤道大西洋海域では東の貿易風が強まる。その結果、冬にエルニーニョが頂点に達した後の春夏に東赤道大西洋では異常な寒冷化が起きる場合がある[85]。両方の海洋におけるエルニーニョに似た現象は、モンスーンの雨が長期間降らないことに関連した深刻な飢饉も引き起こしている[86]。

地域別の影響

編集1950年以降のエルニーニョ現象の観測によると、エルニーニョ現象に関連する影響は時期によって異なる[87]。ただし、エルニーニョ期間に発生する事象や影響は予想されてはいるものの確実ではなく、発生するとの保証はできない[87]。大部分のエルニーニョ現象の最中に概ね発生する影響としては、インドネシアと南米の北部で降雨量が平均を下回り、南米の南東部と東赤道アフリカと米国南部では降雨量が平均を上回る[87]。

アフリカ

編集アフリカでは、ケニア、タンザニア、白ナイル川の盆地を含む東アフリカで3月から5月にかけて長雨となり、平年よりも多雨になる。南中部アフリカでは、ザンビア、ジンバブエ、モザンビーク、ボツワナを中心に、12月から2月にかけて平年よりも少雨になる。

南極大陸

編集南極周辺の高南緯にはENSOとの様々な関連が存在する[88]。具体的には、エルニーニョの状態がアムンゼン海とベリングスハウゼン海に異常高気圧をもたらし、これらの海域ならびにロス海では海氷の減少と極に向かう熱流束の増加を引き起こす。逆にウェッデル海は、エルニーニョの最中により多くの海氷ができて寒くなる傾向がある。ラニーニャの期間ではこれと正反対の加熱および大気圧異常が起こる[89] 。この変動パターンは南極の双極子モード[90]と呼ばれるが、ENSOの影響力に対する変化が南極に偏在しているわけではない[89]。

アジア

編集暖水域が西太平洋やインド洋から東太平洋へと広がるにつれ、そこに雨が降って西太平洋では大規模な干ばつを引き起こし、例年では少雨となる東太平洋に降雨をもたらす。2014年2月にシンガポールは1869年の記録開始以降最も少雨となり、同月の降雨量は僅か6.3mmで気温は2月26日に35°Cにも達した。1968年と2005年もそれに次ぐ乾燥した2月で、降雨量は8.4mmだった。

オーストラリアと南太平洋

編集エルニーニョ現象の最中に、西太平洋からの降雨量遷移がオーストラリア全土の降雨量を減少させる場合がある[12]。大陸南部の上空では、気象体系がより移動性になって高気圧の遮断域が少なくなるため、平均気温を上回る温度が記録される可能性がある[12]。熱帯オーストラリアではインド-オーストラリアのモンスーン発生が2-6週間遅れ、結果として北部の熱帯地方では降雨量が減少することになる[12]。オーストラリア南東部ではエルニーニョ現象に続いて特にインド洋ダイポールモード現象が組み合わさると、森林火災の季節性リスクが大幅に高まる[12]。エルニーニョ現象中に、ニュージーランドでは夏季に強い偏西風が頻繁に発生する傾向があり、東海岸沿いでは例年状態よりも乾燥するリスクが高くなる[91]。ニュージーランドの西海岸では、北島の山脈と南島のサザンアルプスによるバリア効果のため例年よりも多雨になる[91]。

概ねフィジーはエルニーニョ現象中に例年よりも少雨に見舞われ、島の全土が干ばつになることもある[92]。ただし、この島国への主な影響はエルニーニョ現象が確立してから約1年後に体感するものである[92]。サモア諸島では、平均を下回る降雨量と平年より高い気温がエルニーニョ期間に記録され、島の干ばつや森林火災につながる可能性がある[93]。その他の影響としては、海面の低下、海洋環境におけるサンゴ白化の可能性、サモアに影響を与える熱帯低気圧のリスク増加などがある[93]。

欧州

編集ヨーロッパにおけるエルニーニョの影響は、同大陸の天候に影響を与える幾つかの要因の1つであり他の要因がこれを圧倒しうるため、議論の余地はあるものの複雑で分析は困難である[94][95]。

北米

編集北米では、主に気温と降水量へのエルニーニョによる影響が概ね10月から3月にかけて6か月発生する[96][97]。特にカナダの大部分は概ね例年の冬や春よりも穏やかな気候となり、同国東部を除いて重大な影響は起こらない。アメリカ合衆国では、6か月間に以下の影響が概ね観察される。テキサス州からフロリダ州までのメキシコ湾沿いでは雨量が平均を上回り、ハワイ州、オハイオ川渓谷、太平洋北西部、ロッキー山脈では少雨が観察される[96]。

歴史的にエルニーニョは、クリステンセンら(1981)[98]が長期天気予報の科学進展のため情報理論に基づく発見のエントロピーミニマックスパターンを用いるまで、米国の気象パターンに影響を与えるとは理解されていなかった。以前の天候コンピュータモデルは持続性のみに基づいたもので5-7日先にのみ信頼性があり、長期予測は本質的にランダムだった。クリステンセンらは、1年先や数年後でも降水量が平均以下になるか上回かを予測する、些少ながら統計的に有意な技法を実証した。

近年のカリフォルニア州および米国南西部の気象現象研究では、エルニーニョと平均を上回る降水量との間には同現象の強さや別要因に大きく左右される多彩な関係性あることを示している[96]。

テワン風 (Tehuantepecer) の総観状況は、テワンテペク地峡を通って風が加速する寒冷前線の発達をきっかけにメキシコのシエラマドレ・デ・オアハカ山脈で形成される高圧帯と関連がある。テワン風は主に寒冷前線をきっかけに同地域の寒冷期(10月から2月)に発生し、夏季の最大値は7月にアゾレス高気圧の西方進展によって引き起こされる。エルニーニョの冬季は寒冷前線が頻繁にやって来るため、エルニーニョの年における風の強さはラニーニャの年よりも大きい[99]。その影響は数時間から6日ほど継続することがある[100]。一部のエルニーニョ現象は植物の同位体シグネチャに記録されており、このことは科学者達がその影響を研究するのに役立った[101]。

南米

編集エルニーニョの暖水域は上空で雷雨を育てるため、南米西海岸の一部を含む東中部および東太平洋全体の降雨量を増加させる。南米におけるエルニーニョの影響は、北米よりも直接的かつ強大である。エルニーニョはペルー北部とエクアドルの海岸沿いで4月から10月の温暖かつ非常に多雨な気候と関連があり、同現象が強大で極端になるたび大洪水を引き起こす[102]。2月、3月、4月の影響は南米西海岸沿いで危機的になる場合がある。エルニーニョは、大型魚の個体数を維持する冷たくて栄養豊富な水の湧昇を減らしてしまうが、この魚達が(餌となって)豊富な海鳥を維持しており、その鳥の排泄物が肥料産業を支えている。湧昇の減少は、ペルー海岸沖における魚の死に繋がってしまう[103]。

影響を受ける海岸線沿いの地元の漁業は、長期的なエルニーニョ現象の最中に苦難することがある。世界最大規模の漁業は、1972年のエルニーニョの最中に起きたアンチョベータ減少時に乱獲をしたため崩壊した。1982-83年の現象中には、マアジとアンチョベータの個体数が減少し、ホタテは暖かい水で増加したが、メルルーサは大陸斜面の冷水を追いかけ、エビとイワシは南に移動したため、一部の漁獲高が減少したものの増加したものもあった[104]。エルニーニョ現象の最中にこの海域ではサバが増加する。状況の変化による魚の位置や種類の変化が、漁業の課題となっている。ペルーのイワシは、エルニーニョ現象の最中にチリの海域に移動してしまう。他にも1991年にチリ政府が自営業の漁師や産業艦隊向けの漁場に制限を設けるなど、さらに複雑な状況が生じている。

ENSOの変動性は、ペルー沿岸で成長の速い小型種が大幅に増える一因となる場合があり、これは個体数の少ない時期に同海域の捕食者がいなくなるためである。同じ影響で、捕食者の多い熱帯地域から遠方の巣地へと毎春に移動する渡り鳥には有益となる。

ブラジル南部とアルゼンチン北部もまた例年状況に比べて多雨になるが、これは主に春から初夏にかけての間である。チリ中部では降雨量が多い穏やかな冬を迎え、ペルーとボリビア間のアルティプラーノは異常な冬の降雪現象に見舞われたりもする。乾燥した暑い天候は、アマゾン川流域、コロンビア、中央アメリカの一部で発生する[105]。

チリ北部、中部では、夏場に極端な高温、低湿状態が見られる。こうした状況下で、しばしば山火事が発生し(2023年チリ山火事、2024年チリ山火事)、多くの被害が生じている[106][107]。

人類および自然への社会生態学的影響

編集経済効果

編集エルニーニョの状態が何ヶ月も続くと、広範な海洋温暖化と東の貿易風の減少が冷たい栄養豊富な深い水の湧昇を抑制し、国際市場向けの地元漁業における経済的影響が深刻になる恐れがある[103]。

一般的に、エルニーニョは様々な国の商品価格およびマクロ経済に影響を与える可能性がある。エルニーニョは雨が育む農産物の供給を抑制する可能性があり、農業生産、建設、サービス活動を削減したり、食料価格を形成してインフレーションを生じさせたり、主に輸入食品を利用するコモディティ依存の貧困国では社会不安の引き金となる場合もある[108]。ケンブリッジ大学の研究論文では、オーストラリア、チリ、インドネシア、インド、日本、ニュージーランド、南アフリカがエルニーニョ・ショックを受けて経済活動が短命に陥る一方、アルゼンチン、カナダ、メキシコ、米国など他の国々では実際のところエルニーニョ気象ショックの恩恵を(主要貿易相手国からの積極的な波及を通じて直接的または間接的に)受ける場合がある。 さらに、大部分の国々はエルニーニョ・ショック後に短期的なインフレ圧力を受け、世界のエネルギー価格と非燃料コモディティ価格が上昇してしまう[109]。IMFは、1回の大きなエルニーニョが米国のGDPを約0.5%押し上げ(主に暖房費の削減による)、インドネシアのGDPを約1.0%削減しうると推算している[110]。

健康影響や社会的影響

編集エルニーニョの周期に関連した極端な気象状況は、流行性疾患の発生率の変化と相関がある。例えば、エルニーニョの周期は、マラリア、デング熱、リフトバレー熱など蚊によって伝染する病気のリスク増加と関連がある[111]。インド、ベネズエラ、ブラジル、コロンビアにおけるマラリア周期は、現在エルニーニョと関連がある。別の蚊媒介性疾患であるオーストラリア脳炎(マレーバレー脳炎)のアウトブレイクは、ラニーニャ現象に関連する大雨と洪水の後、オーストラリア南東部の温帯で発生する。 1997 - 98年のエルニーニョの最中にケニア北東部とソマリア南部で極度の降雨が発生し、リフトバレー熱の深刻な突発感染が起こった[112]。

またENSOの状態が、北太平洋を横切る対流圏の風と連携したことで[113]、日本や米国西海岸における川崎病の発生率とも関連性があったとする研究もある[114]。

このほか内戦と関連している可能性もある。コロンビア大学地球研究所の科学者達は1950 - 2004年までのデータを解析し、1950年以降のあらゆる内戦の21%でENSOが何らかの役割を果たした可能性を示唆しており、エルニーニョの影響を受ける国では、ラニーニャ年に比べて内戦発生のリスクが年間3%から6%に倍増するという[115][116]。

生態学的な帰着

編集陸上生態系では、1972-73年エルニーニョ現象の後チリ北部およびペルー海岸の砂漠沿いでげっ歯類の突発的増殖が観測された[要出典]。一部の夜行性霊長類(ニシメガネザルとスンダスローロリス)とマレーグマ はこれらの消失した森林内で局所的に絶滅したか大幅に数が減少した。鱗翅目の突発的増殖はパナマとコスタリカで文書化された[要出典]。1982-83,1997-98,2015-16年のENSO現象では、熱帯林の大規模拡大が長期間の少雨を経験して広範囲に火災が発生し、アマゾンとボルネオの森林では森林構造と構成樹木種が劇的に変化した。ただし、2015-16年のエルニーニョ期間では極端な干ばつおよび森林火災後に昆虫個体数の減少が観察されたため、その影響は植生だけに留まらない[117]。アマゾンの焼失森林では、特殊な生息地にいたり環境の乱れに敏感な鳥類や大型哺乳類の減少も見られ、ボルネオ島の焼失した森林では100種以上の低地蝶種の一時的な消失が起こった。

最も危機的なものでは、世界規模の大量サンゴ白化現象 が1997-98年と2015-16年に記録され、生体サンゴの約75-99%に及ぶ損失が世界中で記録された。ペルーとチリのカタクチイワシ科個体数崩壊にも相当な注意が払われ、1972-73,1982-83,1997-98年そして近年では2015-16年のENSO現象後に深刻な漁業危機を引き起こした。特に1982-83年の海面温度上昇はパナマで2種のヒドロサンゴが絶滅した可能性があり、チリでは海岸線600kmに沿って昆布床が大量に死亡、これは20年経っても昆布および関連の生物多様性が最も影響を受けた海域となったが徐々に回復した。これら全ての調査結果から、エルニーニョおよびラニーニャを引き起こすENSOは世界中の生態学的変化(特に熱帯林やサンゴ礁における生態学的変化)を後押しする強大な気候力だと捉えられている[118]。

関連項目

編集脚注

編集注釈

編集出典

編集- ^ 気象庁「よくある質問(エルニーニョ/ラニーニャ現象)」2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ 気象庁「エルニーニョ/ラニーニャ現象とは」2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ Changnon, Stanley A (2000). El Nino 1997-98 The Climate Event of The Century. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 35. ISBN 0-19-513552-0

- ^ Climate Prediction Center (19 December 2005). “Frequently Asked Questions about El Niño and La Niña”. National Centers for Environmental Prediction. 27 August 2009時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。17 July 2009閲覧。

- ^ K.E. Trenberth; P.D. Jones; P. Ambenje; R. Bojariu; D. Easterling; A. Klein Tank; D. Parker; F. Rahimzadeh et al.. “Observations: Surface and Atmospheric Climate Change”. In Solomon, S.; D. Qin; M. Manning et al.. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. The contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 235?336

- ^ “El Nino Information”. California Department of Fish and Game, Marine Region. 2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ “The Strongest El Nino in Decades Is Going to Mess With Everything”. Bloomberg.com. (21 October 2015) 18 February 2017閲覧。

- ^ “How the Pacific Ocean changes weather around the world” (英語). Popular Science 19 February 2017閲覧。

- ^ Trenberth, Kevin E (December 1997). “The Definition of El Niño”. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 78 (12): 2771-2777. Bibcode: 1997BAMS...78.2771T. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<2771:TDOENO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ “Australian Climate Influences: El Nino”. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 4 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ a b “What is the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in a nutshell?”. ENSO Blog (5 May 2014). 9 April 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。7 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ a b c d e f g “What is El Niño and what might it mean for Australia?”. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 18 March 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。10 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ a b “El Nino here to stay”. BBC News. (7 November 1997) 1 May 2010閲覧。

- ^ a b c d “Historical El Niño/La Niña episodes (1950-present)”. United States Climate Prediction Center (1 February 2019). 15 March 2019閲覧。

- ^ a b c “El Nino - Detailed Australian Analysis”. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 3 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/images/El-Nino-in-Australia.pdf

- ^ “December's ENSO Update: Close, but no cigar”. ENSO Blog (4 December 2014). 22 March 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ “ENSO Tracker: About ENSO and the Tracker”. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 4 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ “How will we know when an El Nino has arrived?”. ENSO Blog (27 May 2014). 22 March 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ 気象庁「エルニーニョ監視速報の構成」2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ “Historical El Niño and La Niña Events”. Japan Meteorological Agency. 4 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ “ENSO + Climate Change = Headache”. ENSO Blog (11 September 2014). 18 April 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ Collins, Mat; An, Soon-Il; Cai, Wenju; Ganachaud, Alexandre; Guilyardi, Eric; Jin, Fei-Fei; Jochum, Markus; Lengaigne, Matthieu et al. (23 May 2010). “The impact of global warming on the tropical Pacific Ocean and El Ni?o”. Nature Geoscience 3 (6): 391?397. Bibcode: 2010NatGe...3..391C. doi:10.1038/ngeo868.

- ^ Bourget, Steve (3 May 2016) (英語). Sacrifice, Violence, and Ideology Among the Moche: The Rise of Social Complexity in Ancient Peru. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9781477308738

- ^ Brian Donegan (14 March 2019). “El Nino Conditions Strengthen, Could Last Through Summer”. The Weather Company. 15 March 2019閲覧。

- ^ “El Nino is over, NOAA says”. Al.com (8 August 2019). 5 September 2019閲覧。

- ^ Climate Prediction Center (19 December 2005). “ENSO FAQ: How often do El Niño and La Niña typically occur?”. National Centers for Environmental Prediction. 27 August 2009時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。26 July 2009閲覧。

- ^ National Climatic Data Center (June 2009). “El Nino / Southern Oscillation (ENSO) June 2009”. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 26 July 2009閲覧。

- ^ Kim, WonMoo; Wenju Cai (2013). “Second peak in the far eastern Pacific sea surface temperature anomaly following strong El Nino events”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40 (17): 4751-4755. Bibcode: 2013GeoRL..40.4751K. doi:10.1002/grl.50697.

- ^ Carrè, Matthieu et al. (2005). “Strong El Niño events during the early Holocene: stable isotope evidence from Peruvian sea shells”. The Holocene 15 (1): 42–7. Bibcode: 2005Holoc..15...42C. doi:10.1191/0959683605h1782rp.

- ^ Brian Fagan (1999). Floods, Famines and Emperors: El Nino and the Fate of Civilizations. Basic Books. pp. 119-138. ISBN 978-0-465-01120-9

- ^ Grove, Richard H. (1998). “Global Impact of the 1789-93 El Nino”. Nature 393 (6683): 318-9. Bibcode: 1998Natur.393..318G. doi:10.1038/30636.

- ^ Ó Gráda, C. (2009). “Ch. 1: The Third Horseman”. Famine: A Short History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691147970. オリジナルの12 January 2016時点におけるアーカイブ。 3 March 2010閲覧。

- ^ “Dimensions of need - People and populations at risk”. Fao.org. 28 July 2015閲覧。

- ^ Carrillo, Camilo N. (1892) "Disertación sobre las corrientes oceánicas y estudios de la correinte Peruana ó de Humboldt" (Dissertation on the ocean currents and studies of the Peruvian, or Humboldt's, current), Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, 2 : 72–110. [in Spanish] From p. 84: "Los marinos paiteños que navegan frecuentemente cerca de la costa y en embarcaciones pequeñas, ya al norte ó al sur de Paita, conocen esta corriente y la denomination Corriente del Niño, sin duda porque ella se hace mas visible y palpable después de la Pascua de Navidad." (The sailors [from the city of] Paita who sail often near the coast and in small boats, to the north or the south of Paita, know this current and call it "the current of the Boy [el Niño]", undoubtedly because it becomes more visible and palpable after the Christmas season.)

- ^ Lartigue (1827) (フランス語). Description de la C?te Du P?rou, Entre 19° et 16° 20' de Latitude Sud, ... [Description of the Coast of Peru, Between 19° and 16° 20' South Latitude, ...]. Paris, France: L'Imprimerie Royale. pp. 22-23 From pp. 22-23: "Il est néanmoins nécessaire, au sujet de cette règle générale, de faire part d'une exception ... dépassé le port de sa destination de plus de 2 ou 3 lieues; ... " (It is nevertheless necessary, with regard to this general rule, to announce an exception which, in some circumstances, might shorten the sailing. One said above that the breeze was sometimes quite fresh [i.e., strong], and that then the counter-current, which bore southward along the land, stretched some miles in length; it is obvious that one will have to tack in this counter-current, whenever the wind's force will permit it and whenever one will not have gone past the port of one's destination by more than 2 or 3 leagues; ...)

- ^ a b Pezet, Federico Alfonso (1896), “The Counter-Current "El Niño," on the Coast of Northern Peru”, Report of the Sixth International Geographical Congress: Held in London, 1895, Volume 6, pp. 603-606

- ^ Findlay, Alexander G. (1851). A Directory for the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean -- Part II. The Islands, Etc., of the Pacific Ocean. London: R. H. Laurie. p. 1233. "M. Lartigue is among the first who noticed a counter or southerly current."

- ^ "Droughts in Australia: Their causes, duration, and effect: The views of three government astronomers [R.L.J. Ellery, H.C. Russell, and C. Todd]," The Australasian (Melbourne, Victoria), 29 December 1888, pp. 1455?1456. From p. 1456: Archived 16 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. "Australian and Indian Weather" : "Comparing our records with those of India, I find a close correspondence or similarity of seasons with regard to the prevalence of drought, and there can be little or no doubt that severe droughts occur as a rule simultaneously over the two countries."

- ^ Lockyer, N. and Lockyer, W.J.S. (1904) "The behavior of the short-period atmospheric pressure variation over the Earth's surface," Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 73 : 457-470.

- ^ Eguiguren, D. Victor (1894) "Las lluvias de Piura" (The rains of Piura), Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, 4 : 241-258. [in Spanish] From p. 257: "Finalmente, la época en que se presenta la corriente de Niño, es la misma de las lluvias en aquella región." (Finally, the period in which the El Niño current is present is the same as that of the rains in that region [i.e., the city of Piura, Peru].)

- ^ Pezet, Federico Alfonso (1896) "La contra-corriente "El Niño", en la costa norte de Perú" (The counter-current "El Niño", on the northern coast of Peru), Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de Lima, 5 : 457-461. [in Spanish]

- ^ Walker, G. T. (1924) "Correlation in seasonal variations of weather. IX. A further study of world weather," Memoirs of the Indian Meteorological Department, 24 : 275-332. From p. 283: "There is also a slight tendency two quarters later towards an increase of pressure in S. America and of Peninsula [i.e., Indian] rainfall, and a decrease of pressure in Australia : this is part of the main oscillation described in the previous paper* which will in future be called the 'southern' oscillation." Available at: Royal Meteorological Society Archived 18 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ “Who Discovered the El Nino-Southern Oscillation?”. Presidential Symposium on the History of the Atmospheric Sciences: People, Discoveries, and Technologies. American Meteorological Society (AMS). 1 December 2015時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。18 December 2015閲覧。

- ^ Trenberth, Kevin E.; Hoar, Timothy J. (January 1996). “The 1990-95 El Niño-Southern Oscillation event: Longest on record”. Geophysical Research Letters 23 (1): 57-60. Bibcode: 1996GeoRL..23...57T. doi:10.1029/95GL03602.

- ^ Trenberth, K. E. et al. (2002). “Evolution of El Niño - Southern Oscillation and global atmospheric surface temperatures”. Journal of Geophysical Research 107 (D8): 4065. Bibcode: 2002JGRD..107.4065T. doi:10.1029/2000JD000298.

- ^ Marshall, Paul; Schuttenberg, Heidi (2006). A reef manager's guide to coral bleaching. Townsville, Qld.: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. ISBN 978-1-876945-40-4

- ^ Trenberth, Kevin E; Stepaniak, David P (April 2001). “Indices of El Nino Evolution”. Journal of Climate 14 (8): 1697-1701. Bibcode: 2001JCli...14.1697T. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<1697:LIOENO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Johnson, Nathaniel C (July 2013). “How Many ENSO Flavors Can We Distinguish?*”. Journal of Climate 26 (13): 4816-4827. Bibcode: 2013JCli...26.4816J. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00649.1.

- ^ a b c d “ENSO Flavor of the Month”. ENSO Blog (16 October 2014). 24 April 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ a b Kao, Hsun-Ying; Jin-Yi Yu (2009). “Contrasting Eastern-Pacific and Central-Pacific Types of ENSO”. J. Climate 22 (3): 615-632. Bibcode: 2009JCli...22..615K. doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2309.1.

- ^ Larkin, N. K.; Harrison, D. E. (2005). “On the definition of El Nino and associated seasonal average U.S. Weather anomalies”. Geophysical Research Letters 32 (13): L13705. Bibcode: 2005GeoRL..3213705L. doi:10.1029/2005GL022738.

- ^ 山形俊男「エルニーニョモドキ (新用語解説)」『天気』日本気象学会、2011年3月、48-50頁

- ^ Ashok, K.; S. K. Behera; S. A. Rao; H. Weng & T. Yamagata (2007). “El Nino Modoki and its possible teleconnection”. Journal of Geophysical Research 112 (C11): C11007. Bibcode: 2007JGRC..11211007A. doi:10.1029/2006JC003798.

- ^ Weng, H.; K. Ashok; S. K. Behera; S. A. Rao & T. Yamagata (2007). “Impacts of recent El Nino Modoki on dry/wet condidions in the Pacific rim during boreal summer”. Clim. Dyn. 29 (2?3): 113?129. Bibcode: 2007ClDy...29..113W. doi:10.1007/s00382-007-0234-0.

- ^ Ashok, K.; T. Yamagata (2009). “The El Nino with a difference”. Nature 461 (7263): 481-484. Bibcode: 2009Natur.461..481A. doi:10.1038/461481a. PMID 19779440.

- ^ Michele Marra (1 January 2002). Modern Japanese Aesthetics: A Reader. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2077-0

- ^ Hye-Mi Kim; Peter J. Webster; Judith A. Curry (2009). “Impact of Shifting Patterns of Pacific Ocean Warming on North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones”. Science 325 (5936): 77-80. Bibcode: 2009Sci...325...77K. doi:10.1126/science.1174062. PMID 19574388.

- ^ Nicholls, N. (2008). “Recent trends in the seasonal and temporal behaviour of the El Nino Southern Oscillation”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (19): L19703. Bibcode: 2008GeoRL..3519703N. doi:10.1029/2008GL034499.

- ^ McPhaden, M.J.; Lee, T.; McClurg, D. (2011). “El Nino and its relationship to changing background conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (15): L15709. Bibcode: 2011GeoRL..3815709M. doi:10.1029/2011GL048275.

- ^ Giese, B.S.; Ray, S. (2011). “El Nino variability in simple ocean data assimilation (SODA), 1871?2008”. J. Geophys. Res. 116 (C2): C02024. Bibcode: 2011JGRC..116.2024G. doi:10.1029/2010JC006695.

- ^ Newman, M.; Shin, S.-I.; Alexander, M.A. (2011). “Natural variation in ENSO flavors”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (14): L14705. Bibcode: 2011GeoRL..3814705N. doi:10.1029/2011GL047658.

- ^ Yeh, S.-W.; Kirtman, B.P.; Kug, J.-S.; Park, W.; Latif, M. (2011). “Natural variability of the central Pacific El Nino event on multi-centennial timescales”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (2): L02704. Bibcode: 2011GeoRL..38.2704Y. doi:10.1029/2010GL045886.

- ^ Hanna Na; Bong-Geun Jang; Won-Moon Choi; Kwang-Yul Kim (2011). “Statistical simulations of the future 50-year statistics of cold-tongue El Nino and warm-pool El Nino”. Asia-Pacific J. Atmos. Sci. 47 (3): 223-233. Bibcode: 2011APJAS..47..223N. doi:10.1007/s13143-011-0011-1.

- ^ L'Heureux, M.; Collins, D.; Hu, Z.-Z. (2012). “Linear trends in sea surface temperature of the tropical Pacific Ocean and implications for the El Nino-Southern Oscillation”. Climate Dynamics 40 (5-6): 1-14. Bibcode: 2013ClDy...40.1223L. doi:10.1007/s00382-012-1331-2.

- ^ Lengaigne, M.; Vecchi, G. (2010). “Contrasting the termination of moderate and extreme El Niño events in coupled general circulation models”. Climate Dynamics 35 (2-3): 299-313. Bibcode: 2010ClDy...35..299L. doi:10.1007/s00382-009-0562-3.

- ^ Takahashi, K.; Montecinos, A.; Goubanova, K.; Dewitte, B. (2011). “ENSO regimes: Reinterpreting the canonical and Modoki El Niño”. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38 (10): L10704. Bibcode: 2011GeoRL..3810704T. doi:10.1029/2011GL047364. hdl:10533/132105.

- ^ S. George Philander (2004). Our Affair with El Nino: How We Transformed an Enchanting Peruvian Current Into a Global Climate Hazard. ISBN 978-0-691-11335-7

- ^ “Study Finds El Ninos are Growing Stronger”. NASA. 3 August 2014閲覧。

- ^ Takahashi, K.; Montecinos, A.; Goubanova, K.; Dewitte, B. (2011). “Reinterpreting the Canonical and Modoki El Nino”. Geophysical Research Letters 38 (10): n/a. Bibcode: 2011GeoRL..3810704T. doi:10.1029/2011GL047364. hdl:10533/132105.

- ^ Different Impacts of Various El Nino Events (PDF) (Report). NOAA.

- ^ Central Pacific El Nino on US Winters (Report). IOP Science. 2014年8月3日閲覧。.

- ^ Monitoring the Pendulum (Report). IOP Science. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aac53f。

- ^ “El Nino's Bark is Worse than its Bite”. The Western Producer 11 January 2019閲覧。

- ^ “El Niño and La Niña”. New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (27 February 2007). 19 March 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。11 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ Emily Becker (2016). “How Much Do El Niño and La Niña Affect Our Weather? This fickle and influential climate pattern often gets blamed for extreme weather. A closer look at the most recent cycle shows that the truth is more subtle”. Scientific American 315 (4): 68-75. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1016-68. PMID 27798565.

- ^ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2006年). “3.3 JTWC Forecasting Philosophies”. 11 February 2007閲覧。

- ^ a b Wu, M. C.; Chang, W. L.; Leung, W. M. (2004). “Impacts of El Nino-Southern Oscillation Events on Tropical Cyclone Landfalling Activity in the Western North Pacific”. Journal of Climate 17 (6): 1419-28. Bibcode: 2004JCli...17.1419W. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<1419:ioenoe>2.0.co;2.

- ^ a b c d Landsea, Christopher W; Dorst, Neal M (1 June 2014). “Subject: G2) How does El Nino-Southern Oscillation affect tropical cyclone activity around the globe?”. Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Question. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hurricane Research Division. オリジナルの9 October 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。

- ^ a b “Background Information: East Pacific Hurricane Outlook”. United States Climate Prediction Center (27 May 2015). 7 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ "Southwest Pacific Tropical Cyclone Outlook: El Niño expected to produce severe tropical storms in the Southwest Pacific" (Press release). New Zealand National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. 14 October 2015. 2015年12月12日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2014年10月22日閲覧。

- ^ "El Nino is here!" (Press release). Tonga Ministry of Information and Communications. 11 November 2015. 2017年10月25日時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2016年5月8日閲覧。

- ^ Enfield, David B.; Mayer, Dennis A. (1997). “Tropical Atlantic sea surface temperature variability and its relation to El Ni?o-Southern Oscillation”. Journal of Geophysical Research 102 (C1): 929?945. Bibcode: 1997JGR...102..929E. doi:10.1029/96JC03296.

- ^ Lee, Sang-Ki; Chunzai Wang (2008). “Why do some El Ni?os have no impact on tropical North Atlantic SST?”. Geophysical Research Letters 35 (L16705): L16705. Bibcode: 2008GeoRL..3516705L. doi:10.1029/2008GL034734.

- ^ Latif, M.; Grötzner, A. (2000). “The equatorial Atlantic oscillation and its response to ENSO”. Climate Dynamics 16 (2-3): 213-218. Bibcode: 2000ClDy...16..213L. doi:10.1007/s003820050014.

- ^ Davis, Mike (2001). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. London: Verso. p. 271. ISBN 978-1-85984-739-8

- ^ a b c “How ENSO leads to a cascade of global impacts”. ENSO Blog (19 May 2014). 26 May 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ Turner, John (2004). “The El Ni?o-Southern Oscillation and Antarctica”. International Journal of Climatology 24 (1): 1-31. Bibcode: 2004IJCli..24....1T. doi:10.1002/joc.965.

- ^ a b Yuan, Xiaojun (2004). “ENSO-related impacts on Antarctic sea ice: a synthesis of phenomenon and mechanisms”. Antarctic Science 16 (4): 415-425. Bibcode: 2004AntSc..16..415Y. doi:10.1017/S0954102004002238.

- ^ 気象庁「気候現象及びそれらの将来の地域的な気候変動との関連性」『IPCC第5次評価報告書』14章、56頁。

- ^ a b “El Niño's impacts on New Zealand's climate”. New Zealand's National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (19 October 2015). 19 March 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。11 April 2016閲覧。

- ^ a b “ENSO Update, Weak La Nina Conditions Favoured”. Fiji Meteorological Service. 7 November 2017時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ a b “Climate Summary January 2016”. Samoa Meteorology Division, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (January 2016). 2021年5月2日閲覧。

- ^ “What are the prospects for the weather in the coming winter?”. Met Office News Blog. United Kingdom Met Office (29 October 2015). 20 April 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ Ineson, S.; Scaife, A. A. (7 December 2008). “The role of the stratosphere in the European climate response to El Niño”. Nature Geoscience 2 (1): 32-36. Bibcode: 2009NatGe...2...32I. doi:10.1038/ngeo381.

- ^ a b c “United States El Nino Impacts”. ENSO Blog (12 June 2014). 26 May 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ “With El Nino likely, what climate impacts are favored for this summer?”. ENSO Blog (12 June 2014). 30 March 2016時点のオリジナルよりアーカイブ。2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ Ronald A. Christensen and Richard F. Eilbert and Orley H. Lindgren and Laurel L. Rans (1981). “Successful Hydrologic Forecasting for California Using an Information Theoretic Model”. Journal of Applied Meteorology 20 (6): 706-712. Bibcode: 1981JApMe...20.706C. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1981)020<0706:SHFFCU>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Rosario Romero-Centeno; Jorge Zavala-Hidalgo; Artemio Gallegos; James J. O'Brien (August 2003). “Isthmus of Tehuantepec wind climatology and ENSO signal”. Journal of Climate 16 (15): 2628-2639. Bibcode: 2003JCli...16.2628R. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016<2628:IOTWCA>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Paul A. Arnerich. “Tehuantepecer Winds of the West Coast of Mexico”. Mariners Weather Log 15 (2): 63-67.

- ^ Martínez-Ballesté, Andrea; Ezcurra, Exequiel (2018). “Reconstruction of past climatic events using oxygen isotopes in Washingtonia robusta growing in three anthropic oases in Baja California”. Boletín de la Sociedad Geológica Mexicana 70 (1): 79-94. doi:10.18268/BSGM2018v70n1a5.

- ^ “Atmospheric Consequences of El Nino”. University of Illinois. 31 May 2010閲覧。

- ^ a b WW2010 (28 April 1998). “El Nino”. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 17 July 2009閲覧。

- ^ Pearcy, W. G.; Schoener, A. (1987). “Changes in the marine biota coincident with the 1982-83 El Nino in the northeastern subarctic Pacific Ocean”. Journal of Geophysical Research 92 (C13): 14417-28. Bibcode: 1987JGR....9214417P. doi:10.1029/JC092iC13p14417.

- ^ Sharma, P. D.; P.D, Sharma (2012) (英語). Ecology And Environment. Rastogi Publications. ISBN 978-81-7133-905-1

- ^ “チリで森林火災、56人死亡 気温上昇で消火困難に”. 日本経済新聞 (2024年2月4日). 2024年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “南米・チリ、大規模森林火災 少なくとも122人死亡 人為的な可能も”. 日テレニュース (2024年2月6日). 2024年5月27日閲覧。

- ^ “Study reveals economic impact of El Nino”. University of Cambridge (11 July 2014). 25 July 2014閲覧。

- ^ Cashin, Paul; Mohaddes, Kamiar & Raissi, Mehdi (2014). “Fair Weather or Foul? The Macroeconomic Effects of El Nino”. Cambridge Working Papers in Economics. オリジナルの28 July 2014時点におけるアーカイブ。.

- ^ “Fair Weather or Foul? The Macroeconomic Effects of El Nino”. 2021年12月30日閲覧。

- ^ “El Nino and its health impact”. allcountries.org. 10 October 2017閲覧。

- ^ “El Nino and its health impact”. Health Topics A to Z. 1 January 2011閲覧。

- ^ Rodó, Xavier; Joan Ballester; Dan Cayan; Marian E. Melish; Yoshikazu Nakamura; Ritei Uehara; Jane C. Burns (10 November 2011). “Association of Kawasaki disease with tropospheric wind patterns”. Scientific Reports 1: 152. Bibcode: 2011NatSR...1E.152R. doi:10.1038/srep00152. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 3240972. PMID 22355668.

- ^ Ballester, Joan; Jane C. Burns; Dan Cayan; Yosikazu Nakamura; Ritei Uehara; Xavier Rodó (2013). “Kawasaki disease and ENSO-driven wind circulation”. Geophysical Research Letters 40 (10): 2284-2289. Bibcode: 2013GeoRL..40.2284B. doi:10.1002/grl.50388.

- ^ Hsiang, S. M.; Meng, K. C.; Cane, M. A. (2011). “Civil conflicts are associated with the global climate”. Nature 476 (7361): 438?441. Bibcode: 2011Natur.476..438H. doi:10.1038/nature10311. PMID 21866157.

- ^ Quirin Schiermeier (2011). “Climate cycles drive civil war”. Nature 476: 406?407. doi:10.1038/news.2011.501.

- ^ França, Filipe; Ferreira, J; Vaz-de-Mello, FZ; Maia, LF; Berenguer, E; Palmeira, A; Fadini, R; Louzada, J et al. (10 February 2020). “El Niño impacts on human-modified tropical forests: Consequences for dung beetle diversity and associated ecological processes”. Biotropica 52 (1): 252-262. doi:10.1111/btp.12756.

- ^ França, FM; Benkwitt, CE; Peralta, G; Robinson, JPW; Graham, NAJ; Tylianakis, JM; Berenguer, E; Lees, AC et al. (2020). “Climatic and local stressor interactions threaten tropical forests and coral reefs”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 375 (1794): 20190116. doi:10.1098/rstb.2019.0116. PMC 7017775. PMID 31983328.

外部リンク

編集- 気象庁「エルニーニョ/ラニーニャ現象」

- “Current map of sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific Ocean”. earth.nullschool.net. 2021年12月30日閲覧。

- “Southern Oscillation diagnostic discussion”. United States National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. 2021年12月30日閲覧。